Contemporary politics is highly polarised. Ours is the age of binaries and divisions of convenience. The Right-Left binary that originated in the times of the French Revolution when liberal deputies of the Third Estate would generally sit to the left of the presiding officer’s chair while the nobility (the Second Estate) would sit to the right, in a custom that began in the Estates General in 1789, has become the premise of delineating party politics and ideology the world over. In all this, while the Left maintains a certain identity and unity on what it stands for, a glaring question is: Is there an international Right wing? Norberto Bobbio, might I add rather controversially, posited that the right wing has traditionally been seen as being supportive of certain social structures that promote hierarchies, if not outright inequality, seeing it as the natural order of things. This binary copula was developed into one involving inclusion and exclusion by Alessandro Pizzorno, who famously said in an interview in 1995

“What matters to the individual is knowing whether he is excluded or accepted, whether or not he is considered as being equal to the others.”

Ref: Gnoli, Antonio. Caro Bobbio, ecco dove sbagli. La Repubblica. 1995.

The idea that there is a certain `otherness’ defined could be due to ingrained social differences or class structures arising in market economies, among other possible causes. This binary has been fluid many-a-times, with British politics being a prime example of the same: the Right and the Left have seemingly had a synchronised movement towards and away from the centre over the decades (not-quite-centrist John Smith became leader of the Labour party to counter the post-Thatcherite John Major years for the Conservatives, which was fairly Right wing, even as a centrist like David Cameron came to the Conservative helm-of-affairs to counter the Blairite centrism in the Labour party) .

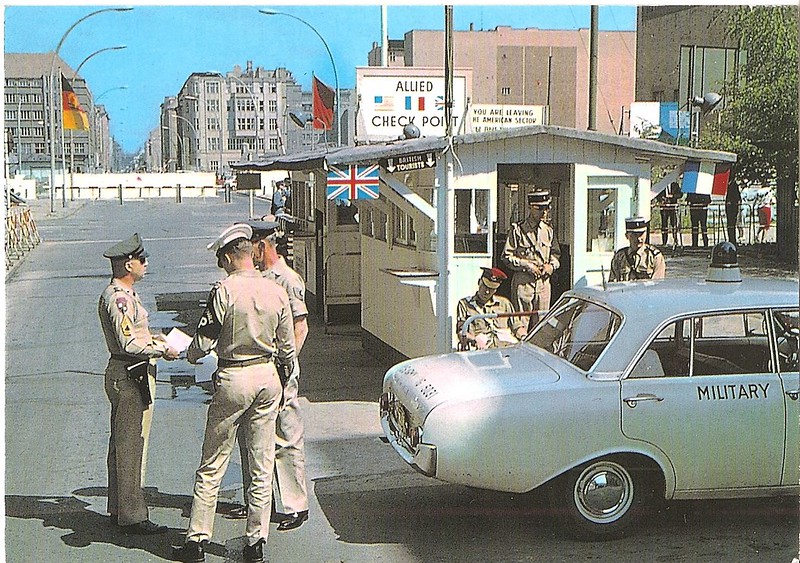

This fluidity, nay the near-dissolution of distinctions, is particularly expressed when one of the sides of the proverbial aisle becomes predominant. This is primarily because then the dominant sides tries to project that there is no real alternative while the weaker side has its interest in playing down any differences with the dominant side. The Right, for one, has not always been as strong as it is in many parts of the world today. After the second world war, with the fall of Nazi Germany and Italian Fascism, people widely supported collectivist ideals and Right-of-Centre parties such as the Christian Democrats had to atleast pretend to align with values like social cohesion. More generally, the Left-Right binary is dynamic and in one age is not necessarily the same as in another, not due to a vacuity in meaning but rather due to relativity and context.

The Intricacies of Inclusivity and Freedom

The Right and the Left do not represent any fixed ideas but are oriented around a political axis that is calibrated and shifted in various generations. In contemporary politics, the binary has increasingly become just an instrument of antithetical politics: what is not us is them. Historically, and particularly in Pizzorno’s formulation, this kind of politics has annotated a certain preeminence to the idea of egalitarianism (which relates to Bobbio’s egualitarista, which specifically talks of a utopian conception than a pragmatic one), either in a utopian regimentation (where one has equality for everyone in everything) or a more pragmatic idea of the same (which engages with questions like equality between whom, in what and on what basis).

The difference between the Left and the Right has been on the degree of equality-inequality within a specific historical and cultural context. Difference is considered the opposite of regimented equality while inequality is the opposite of pragmatic equality. Difference can be seen as a positive quality, since it facilitates the freedom of every individual to develop his or her unique tendencies and particular natures. An interesting idea that early modern thinkers put forth is that equality and distinct development of individuals need not necessarily be at loggerheads with each other. For instance, Massimo Cacciari once famously said

“Equality makes diversity possible, and makes it possible for everyone to count as a person.”

Ref: Cacciari, M. Dialoghetto sulla “sinisteritas” MicroMega. 1993.

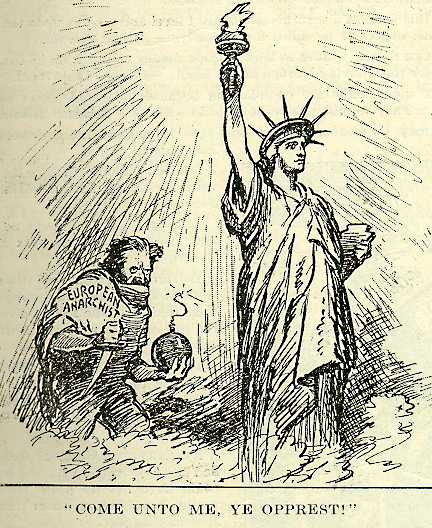

One important point here is that freedom defines autonomy and possibility of an individual to be distinct, and does not belong as a `concept’ to either the Left or the Right, being the individual good that it is. However, these binaries of equality-inequality and inclusion-exclusion have made way to a formulation based on the concept of liberty and social justice. Europe has been guided by the ideal of liberty since the Enlightenment. The conflict between the Left and the Right has increasingly been about what must be given greater emphasis: social rights or libertarian rights. Funnily both have accused the other of having preferred the latter over the former: the Left accuses the Right of having done so at the expense of the interests of a community structure while the Right has accused the Left of doing so at the expense of traditional social constructs.

The modern political Universe comprises of two entirely separate axes: libertarianism/authoritarianism and left/right. We have the extreme and moderate Right and Left, with the extremists usually being viewed as authoritarian. In India, we often see a possible anomaly on this count in the Left which seems to often stand for an extreme egalitarianism that they try to dish out with the ideas of market economy, universal suffrage, tolerance and religious freedom, whose last remaining semblances have also all been dismantled as evident from the given citations. This anomaly is easily resolved by accounting for what Gerrard Winstanley once famously mentioned in his dedication of The Law of Freedom in a Platform (1652) to Oliver Cromwell:

“You have the power … to act for common freedom if you will: I have no power.”

Ref: G. Winstanley , The Law of Freedom and Other Writings. Harmondsworth: Penguin. 1973.

The lack of, or aversion to, take up power, best instantiated by the time when Jyoti Basu did not take the Prime Ministership of the country since his party felt they always wanted to work from outside the government, gives the Indian Left a certain leeway and space to present jarring anomalies in the manner of reconciling extreme egalitarianism with inherently liberal ideas. When they did have power, there have been a number of instances of violence and widespread destruction. Who can forget the violence carried out by communists in India, over the decades. We can also discuss of an interesting instantiation, although quite different in many ways, in the workings of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in India, which has increasingly tried to bring together its strongly revivalist socio-cultural and political advance with inherently liberal and modern tendencies, and in this case, they have done so by curbing and controlling some of the more radical elements in their fold. What has been different in the Sangh’s case is that, while there have been instances of violence during the tenure of the current regime and in the past, clout has not been imposed and misused anywhere close to the extent the red scourge of the communists back in the day, where not just scientific rigging and subversion of democracy was undertaken, even massacres (like the Marachjhapi Massacre) and condescension of inherently Indian elements of life and society (such as religious sentiments and practices) were undertaken.

Trajectory of, and Diversity in, the International Right

The Right wing arose in reaction to the activities of the early Marxist movements, which were in opposition to European monarchies. Some of these monarchies made the advocacy of communism illegal. This included the German, Russian and Austria-Hungary monarchies. These monarchies viewed the hierarchy in wealth and power in society as resulting from a divine natural order. The end of World War I saw the defeat of some of the most powerful monarchies in the world, including the Ottomans and the Germans. The divine right of monarchs gave way to liberalism and nationalism as the primary forces that stood against communism. It is interesting to note that although Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels saw in the concepts of nation state and nationalism a bourgeois tint, so to say, both regarded the creation of the centralized state as a facilitator of positive social conditions that could help stimulate class struggle! Stalin promoted revolutionary patriotism, a civic patriotic concept, while Josip Broz Tito promoted Yugoslavism. However, by the end of the first World War, with Stalin himself embracing a more universal cosmopolitan modernity, the communists gave greater emphasis on internationalism, and therefore, the nationalists who opposed them were invariably placed on the Right. Soon, fascist movements, liberal conservatives and colonial powers replaced the traditional Right, in the opposition to communism.

After the second World War, anti-communism was an important part of the foreign policy of the NATO. The Right, or conservatism to be more precise, started focussing more on traditional values (particularly religious) and on patriotism and nationalism. McCarthyism rose in the US to offset communist influences in the States. Economically, the Right has not had such a clean trajectory. In the early days, the Right was collectivist and against liberalism (with the advocacy of paternalist class harmony). A marked shift took place in the nineteenth century, when the Right started favouring capitalists over the working class, instead of being fixated on traditional structures oriented around the nobility and industrialists, even though this movement was not uniform or straightforward (with some outliers like Carlists in Spain). Even today, while many of us may think that being Right wing means being aligned exclusively with laissez-faire capitalism, that is not true.

Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BSM) is one of the largest trade unions of the world and is an affiliate of the Sangh Parivar. It has often opposed policies of the BJP government that it feels are anti-workers. Here we can see protests over what they see as the dilution of labour laws. Even though both BSM and BJP belong to the Sangh Parivar and attest to similar socio-cultural ideas, they clearly are at great variance economically many-a-times. (Source: The New Indian Express)

Right-wing movements like the American paleoconservatists oppose capitalists even today, since they see them as catalysing the decay of social structures, hierarchies and order. Even though the French Right supported capitalism from the late nineteenth century itself, it was only with Reaganian and Thatcherite political posturing with the neoliberal Right that ideas like liberalisation, privatisation, deregulation and free markets became so deeply intertwined in a significant manner with the traditional Right’s alignment with traditional social constructs, in a curious socio-economic cocktail. Politically, the Right has believed in the idea that the state gets its political legitimacy from a certain organic unity of its citizens, which is built on collectively shared culture, race, religion and language. Culturally, the Right traditionally is conservatist, and supports the idea that heritage of a culture or nation must be preserved. As historian and journalist Rick Perlstein once said

“One of the most important things liberals don’t understand about conservatism, obscured by too much lazy talk about conservatism’s various ‘wings,’ is that its tenets form a relatively organic base for its adherents, where ‘traditional morality’ serves the interests of laissez-faire economics and vice-versa.”

Socially, the Right supports social order and stratification, seeing it as a natural and inevitable occurrence. Social conservatives have a certain commitment to traditional values concerned with family structures, sexuality, patriotism and national security. One of the outlying agendas of social conservatives in India is the institutionalisation of the Uniform Civil Code (a proposal to establish secular personal laws of citizens which apply on all citizens equally regardless of their religion). This is because Hindu nationalists do not perceive of the Hindu identity only as a religious one, if at all in some cases. They regard it as a national and civilisational identity, which needs to be cherished and maintained.

To understand whether we can regard the conservatives and libertarians along with the widely-purported-as-Right parties in India as truly Right wing, we must see what kinds of elements are present in the international Right. The New Right comprises of liberal conservatives who speak of free markets, minimal governance by the state and individual initiative. The reactionary right works with a sense of nostalgia, looking towards the past, and often being authoritarian (possibly aristocratic) and standing with traditional values, particularly religious. The moderates on the Right can tolerate gradual change that incorporates some nuances of liberalism. While they support free markets, capitalism, social welfare, nationalism and the rule of law as important, they also see extreme individualism and radical laissez-faire policies as counterproductive. The radical Right usually involves populists among other subtypes, while the extreme Right is characterised by ultra-nationalism, anti-democratic stances, support for a strong state and possible alignment with racism. More simply, one could talk of the centre-Right and the far-Right. The former is supportive of capitalism and the market economy, liberal democracy, limited welfare state (funnily, it was Otto van Bismarck, a German conservative, who first brought the idea of a pension-based Welfare State, not any communist or Left-wing government!) and private property rights. The latter is more absolutist and seeks to use the power of the state to assert the dominance of a specific religious or ethnic group.

Do we have or need an Indian Right?

Having looked at these myriad aspects of the international Right, the key question is: does India have a Right wing? You must be jeering at me having even asked the question, but a bit more of scrutiny will make clear that it is not as trivial as it may seem to be, as a question. What if I were to say that India has no Right-wing party or homogenous Right-wing political positioning? Ridiculous, you may say! But is it? The Nehruvian socialist model is often purported to be a liability that hampered India’s growth in its early years post-Independence. India has a large middle-class population and an ever-burgeoning young populace, both of which are aspirational. The political significance of aspiration cannot be understated, with it having been the primary premise on which Tony Blair famously rolled out his New Labour campaign back in the 1990s. Are having aspirations a natural way to adopting the economic Right? Some would argue yes. But it is exactly by the Blairite revolution in England that we can see why this is a false premise. Addressing aspirations can be made to go hand-in-hand with a more egalitarian perspective, with a greater emphasis on social justice. We do not have to look too far to see that. In India, any and every government has to do this balancing act if it has to survive. The current government, which is projected as the first government formed by a Right-wing party (the BJP) with an absolute majority on its own, has been a champion of egalitarian welfarism. Be it zero-budget farming, programmes like PMAY-Gramin and Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana, or the measures such as colossal food and fertiliser subsidies (such as in FY21, which touched a whopping Rs. 6.52 lakh crore), the BJP brings forward a certain social consciousness and compassion that it is made to always stand by due to the ethos of the Sangh, which also happens to have the largest workers’ union in the country – the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh. Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, who formulated the set of concepts known as Integral Humanism (which is the official doctrine of the Bharatiya Janata Party), stood by centralised planning along with state ownership of productive activity, having once stated that

“To set the process of economic development moving, to keep the economy on an even keel the state must undertake in general to plan, direct, regulate and control economic effort and in certain specific spheres and circumstances to accept the responsibility of ownership and management too”

In his book Two Plans: Promises, Performances, Prospects, he speaks about the nationalisation of industries

“We not only want the nationalisation of basic industries, but also wish to apply this principle to those industries, which enjoy the monopoly of only a handful of people”

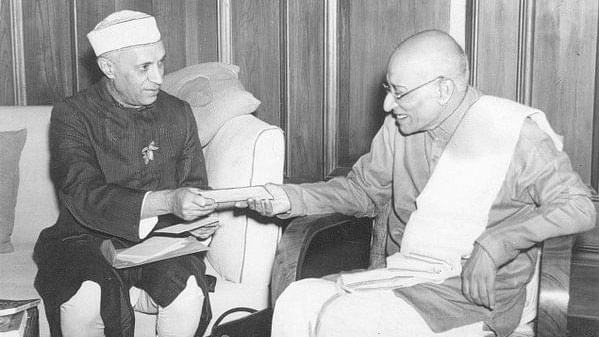

Strange as it may seem, one of the key guiding forefathers of the BJP clearly stood by a path that the likes of Nehru and Indira Gandhi would have quite aligned with! What was, however, very different in his viewpoint was his greater focus on employment generation with small units. He preferred the imposition of low taxes and possibly a slower pace of growth, to facilitate the growth of indigenous small-scale market-players at their own pace. He also spoke against the corruption, hoarding and black-marketing in the way planning was undertaken by the Nehruvian regime. Having said that, there were aspects such as the joint ownership of property between the individual and the state that Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya espoused, and which do not come under the purview of a major cross-section of the traditional international Right. Even luminaries from other cross-sections of the political spectrum have never aligned with any single political lobby or tradition. Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar championed individual freedom but also favoured collective action against caste oppression. Dr. Manmohan Singh was a Nehruvian economist who ushered in the liberalisation of India. Mahatma Gandhi himself was a supporter of moderated Right-wing economics with trusteeships and Swadeshi goods and services but had certain aspects to his life that would not quite make him a social conservative.

The current BJP government is also placed converse to what many libertarians or conservatives would expect from a Right-wing government. The role of the state has seemingly reduced, particularly by using technology to reduce the government-to-citizen interfaces with local bureaucrats, who have traditionally been seen as being corrupt. However, the role of the government overall may well have increased, even as the governments tries to augment such innovations and interventions. This is possibly because the demand of the common man may not be as much on less government but rather on a better and transparent government, which the BJP is trying to deliver. Some of the economic stalwarts aligned with the BJP and the Sangh, such as Dattopant Thengadi and S. Gurumurthy, are also not quite aligned with the libertarian or conservative ideal, in not being dismissive of globalisation but at the same time being strong proponents of the domestic-first model with varying degrees of protectionism, a view that was shared by Veer Savarkar in his push for Swadeshi, and which is best put in his own words

Every step must be taken by the State to protect national industries against foreign competition

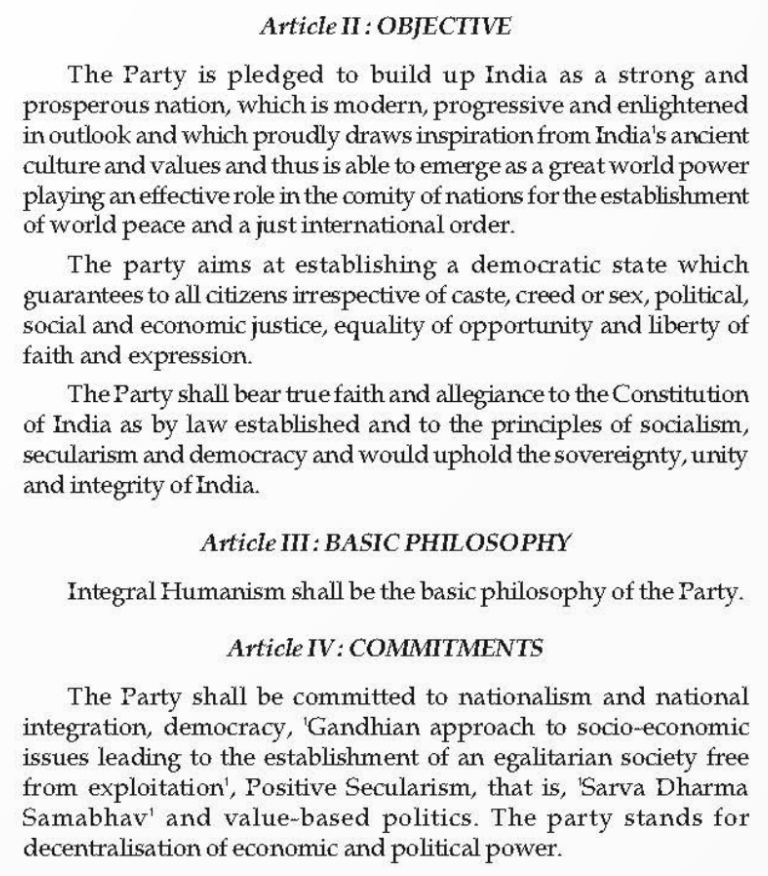

Even the constitution of the BJP has some insightful sections, which highlight the egalitarian push of the party:

(Source: BJP Constitutions)

I think that the government’s push to deliver goods and services to the grassroots, more diverse and critical welfare schemes and programmes, protection of MSMEs and promotion of `Make in India‘, along with pushing for comprehensive economic growth, is a prime example of mixed economy policies and a transcendence of the traditional Left-Right binary. Much like Jean Paul Sartre tried to wed existentialism and Marxism and Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya tried to move beyond the capitalistic-communist binary, the need of the hour is probably to simply have a compassionate and comprehensive governance model, which caters to the unique needs and interests of our nation, moving beyond antiquated western political binaries. Moreover, it is not ridiculously primitive to seek to closet causes such as gender equality, caste parity and climate justice into silos of the Right and Left? I remember the time when my apparently Right-wing alignment was something that some of the Cambridge climate justice warriors had a problem with. Only if I could show them how socially conservative groups like temple trusts in Uttarakhand are helping Left-leaning activists and local governments in protecting the unique ecosystem therein. We must rid ourselves of parochial and regressive ideas of identities and ideologies, particularly around exclusivism. I feel India has a unique opportunity to not ape the international political traditions, like the Indian Left has historically tried to do, and ground its politics in something fundamentally Indic. In the past, I have formulated a novel political philosophy known as Turiyavaad, which paradoxically speaks of transcending the universal angst and desire of individuals to align with dogma or rigid political constructs and philosophies, relying more on evidence-based policy making and the pre-eminence of truth.

It is time to discard the tag of the Right wing and simply go for that which is right for the country!

जय हिन्द

Banner: Public.Resource.org