Even as Narendra Modi and his government goes about with the task of inaugurating a ‘Statue of Unity‘, a colossal 597 ft. tall statue of Sardar Patel, much to the delight and criticism of different sections of the country, I believe the gesture of identifying one of the sutradhar (or the ones who weave the narrative) of India and its modern history is a commendable thing in a country that has been predominantly overshadowed by the Nehru-Gandhi family. Had it not been for Sardar Patel, we may have seen an India today that would have been perforated in the map by swathes of independent countries and states, symbolising the political fabric of the country that had been devoured by the termites of time. Lohpurush (Iron Man of India), as Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was popularly called, once said,“Manpower without Unity is not a strength unless it is harmonized and united properly, then it becomes a spiritual power“. If Nehru was the erudite leader and statesman at the front of the first Indian national government post-independence, Patel was the astute strategist and politician-par-excellence keeping not only the Congress together (by letting Nehru become India’s first Prime Minister, even after having won the popular vote of the Congress Working Committee to lead the government) but also the nation.

After centuries of invasions and foreign rule, the Indian subcontinent was a fractured political entity. Given that there never was an `India’ before 1947 , other than the kingdoms of the Mauryans, Guptas, Mughals and certain other dynasties, the tasks in front of Nehru and Patel was colossal: to unite a nation that had been primarily confined to the conceptions that various leaders and movements had of it! It was primarily Sardar Patel who went about with the task of uniting India, as it stands, with vigor and determination to bring as many princely states into India as possible. Not only did he unite India, but also played a pivotal role in establishing a vision of Independent India by contributing in significant ways to the framing of the Indian constitution. In this article, I would like to look at the life and times of this great Indian and cherish his memories and contribution to the re-awakening of this great nation in the modern age.

India(s), in 1947

In 1947, besides British India, we also had another India: an India that had maintained the semblance of the fractured polity that led to its weak resistance to foreign invasions over the centuries; an India that was ruled by rulers so decadent in certain instances that they could put even modern day acolytes of crony capitalism in their place. With 584 princely states, which were semi-independent and largely dependent on the British Empire for their sustenance, except for a few, this India was a jigsaw puzzle with too many pieces to count. These kingdoms were not under direct British rule but rather under subsidiary alliances and indirect rule. The kingdoms were ruled (all but in name, mostly) by potentates with a variety of titles, such as Maharaja, Raja, Nizam, Nawab, Chhatrapati, Thakur Sahab or Darbar Sahab.

In 1947, only four of the largest of the states still had their own British Residencies (housing British advisors to the local kings) while most of the others were grouped together into Agencies, such as the Central India Agency and the Rajputana Agency. The states had been represented in the Chamber of Princes since 1920. Before leaving, the British gave up their suzerainty of the states and left each of them free to choose whether to join India or Pakistan or to remain outside them. While states like Travancore sought to remain independent, eventually all of them were integrated into either India or Pakistan. However, the journey to that point was far from simple and straightforward, and one that fascinates me, as someone quite interested in Indian history. Let us look at some of the states more closely to truly appreciate the major role played by Patel in uniting India, as it stands.

Junagadh

Mohammad Sher Khan Babi, the first of the kings of the Babi dynasty of Junagadh, founded the state of Junagadh by declaring independence from the Mughals in 1730 after an invasion by the Maratha Gaikwad clan. Possessing large areas in southern Saurashtra, the Junagadh state was entitled to a 13-gun salute by the British Empire. On 15 September 1947, Nawab Mohammad Mahabat Khanji III (Babi) of Junagadh chose to accede to Pakistan, even though Junagadh had no common border with Pakistan and could only access it by sea. The rulers of Mangrol and Babariawad, two states that were subject to the suzerainty of Junagadh, reacted by declaring their independence from Junagadh and acceding to India. In response, Nawab Mohammad Mahabat Khanji III militarily occupied the two states, whereupon rulers of neighbouring states reacted angrily, sending troops to the Junagadh frontier, and appealed to the Government of India for assistance. It was Sardar Patel who believed that if Junagadh was permitted to go to Pakistan, it would exacerbate the communal tension already simmering in Gujarat.

The Indian government thereupon asserted that Junagadh was not contiguous to Pakistan and pointed out that the state was 96% Hindu, and called for a plebiscite to decide the question of accession. India cut off supplies of fuel and coal to Junagadh, and severed air and postal links. Eventually, Patel ordered the forcible annexation of Junagadh’s three principalities, sent troops to the frontier, and occupied the principalities of Mangrol and Babariawad that had acceded to India. On 26 October 1947, the Nawab and his family fled to Pakistan following clashes with Indian troops. It is interesting to note that on around the 7 November 1947, the father of the future Prime Minister of Pakistan Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto – the Dewan of Junagadh, Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto decided to invite the Government of India to intervene and wrote a letter to Mr. Buch, the Regional Commissioner of Saurashtra in the Government of India to this effect. A plebiscite was conducted in February 1948 and Junagadh thereafter officially became part of the Indian state of Saurashtra with a thumping 99% support among the people for accession to India.

Hyderabad

The state was ruled from the early eighteenth century until India’s independence by a hereditary Nizam who was initially a Mughal governor of the Deccan before proclaiming independence. Hyderabad gradually became the first princely state to come under British paramountcy after signing a subsidiary alliance agreement. On 11 June 1947, the Nizam Sir Mir Osman Ali Khan Siddiqi, Asaf Jah VII issued a declaration to the effect that he had decided not to participate in the Constituent Assembly of either Pakistan or India, thereby effectively seeking to rule an independent state and hoped to maintain this with an irregular army recruited from the Muslim aristocracy, known as the Razakars. Besides problems faced by the state such as during the Telangana uprising, the Nizam also had to face the fact that many in the state wanted to accede to India. The Nizam went so far as to appoint trade representatives in European countries and even began negotiations with the Portuguese, seeking to lease or buy Goa to provide his state with access to the sea! Even though Nehru favoured talks and considered military option as a last resort, Patel took a hard line.

Figure: The Nizam of Hyderabad, one of the richest man in the world in his days, featured on the Times magazine

Initially, the Indian government offered Hyderabad a Standstill agreement which made an assurance that the status quo would be maintained and no military action would be taken for a year. According to this agreement India would handle Hyderabad’s foreign affairs, but Indian Army troops stationed in Secunderabad would have to be removed. However even before the agreement was signed, there was a huge demonstration by Razakars led by Syed Qasim Razvi in October 1947 in front of the houses of the main negotiators such as Prime Minister Nawab of Chattari and Minister Nawab Ali Nawaz Jung, against the administration’s decision to sign Standstill Agreement, thereby forcing the administration to call off their Delhi visit to sign the agreement. Moreover, Hyderabad violated all clauses of the agreement, in various ways such as

- In external affairs, it apparently carries out intrigues with Pakistan, to which it secretly loaned £1,50,00,000! Pakistan was planning to use that money to buy arms & ammunition for war against India over the Kashmir issue. In a way, the Nizam of Hyderabad was planning to fund Pakistan army for its war against India. Thanks to Sardar Patel’s timely intervention, Hyderabad was forced to hold the loan sanction to Pakistan till the end of the standstill agreement.

- In defence, by building up a large semi-private army with the Razakars constituting the bulk of this army

- In communications, by interfering with the traffic at the borders and the through traffic of Indian railways

According to Taylor C. Sherman,

India claimed that the government of Hyderabad was edging towards independence by divesting itself of its Indian securities, banning the Indian currency, halting the export of ground nuts, organising illegal gun-running from Pakistan, and inviting new recruits to its army and to its irregular forces, the Razakars.

In the first week of September 1948, Patel called for a high level meeting with Indian Army to explore ways to march troops into Hyderabad and take control as a form of “police action”. Unfortunately, Nehru was not in favour of such “police action”, and even tried to delay the operation, but Patel who was determined to resolve this issue at any cost, bypassed Nehru and gave the green signal to Army to march ahead!

Figure: Razakars

The Nizam was in a weak position, military-wise, as his army numbered only 24,000 men, of whom only around 6,000 were fully trained and equipped. The soldiers included Arabs, Rohillas, North Indian Muslims and Pathans. The State Army consisted of three armoured regiments, a horse cavalry regiment, 11 infantry battalions and artillery, supplemented by irregular units with horse cavalry, four infantry battalions and a garrison battalion. In addition to these, there were about 2,00,000 irregular militia comprising of Razakars under the command of civilian leader Kasim Razvi. A quarter of these were armed with modern small firearms, while the rest were predominantly armed with muzzle-loaders and swords.

The Indian army, on the other hand, came up with the Goddard Plan, which envisaged two main thrusts – from Vijayawada in the east and Solapur in the west – while smaller units pinned down the Hyderabadi army along the border. Two squadrons of Hawker Tempest aircraft were prepared for air support from the Pune base. After heavy combat in Naidurg Fort, Suryapet, Osmanabad, Jalna, Mominabad, Zahirabad and Bidar, it was becoming increasingly clear that the Hyderabad army and the Razakars had been routed on all fronts and had faced extremely heavy casualties. On 17 September the Nizam announced ceasefire thus ending the armed action.

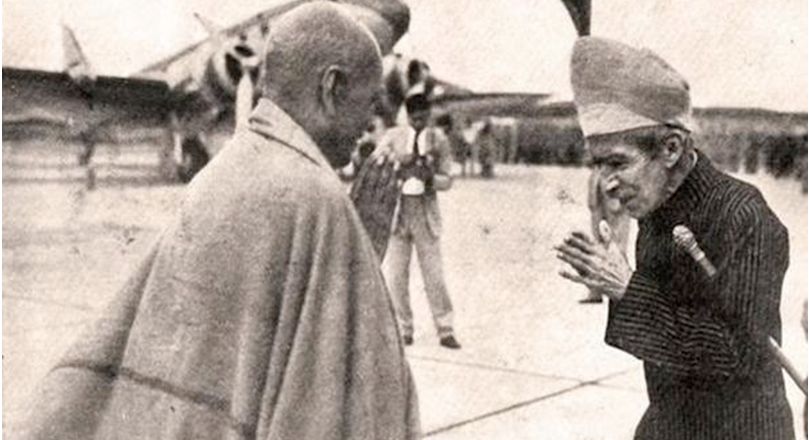

Figure: Sardar Patel with Nizam of Hyderabad

The Nizam of Hyderabad, in his radio speech on 23 September 1948, said

In November last [1947], a small group which had organized a quasi-military organization surrounded the homes of my Prime Minister, the Nawab of Chhatari, in whose wisdom I had complete confidence, and of Sir Walter Monkton, my constitutional Adviser, by duress compelled the Nawab and other trusted ministers to resign and forced the Laik Ali Ministry on me. This group headed by Kasim Razvi had no stake in the country or any record of service behind it. By methods reminiscent of Hitlerite Germany it took possession of the State, spread terror … and rendered me completely helpless.

The Nizam was probably true with 120 murders and 3,59,85,475 instances of loot in 176 villages of Bidar in the Hyderabad-Karnataka region alone by Razakar groups, as per the book `Role of Freedom Fighters in Bidar District (1890-1948)‘ by Dr. Venkat Rao Palati. However, at the end of the day, certain complicity by the Nizam was pinned down by historians.

Bhopal

After India achieved independence on 15 August 1947, Bhopal was one of the last states to sign the Instrument of Accession. The last Nawab Hamidullah Khan expressed his wish to retain Bhopal as a separate independent state in March 1948. The Nawab of Bhopal had ambitions of forming a combined state of princes on par with Pakistan and India. Before he could do much, Sardar Patel moved with alacrity, parallel to Panditji’s activities at calling their bluff. Together they brought the vagrant princes around after they disclosed the role of Nawab of Bhopal as a saboteur. Congress used the Maharajas of Bikaner, Patiala and Cochin to frustrate Sir Hameedullah Khan of Bhopal who was using the chamber of princes as a bargaining lever to protect and perpetuate the princely order.

In his home turf, agitations against the Nawab broke out in December 1948, leading to the arrest of prominent leaders including Bhai Ratan Kumar Gupta and Shankar Dayal Sharma, who later became President of India, and Satyagrahis like Ram Charan Rai, Biharilal Ghatt, Thakur Lalsingh and Laxminarayan Sinhal. After many were shot dead by the Bhopal state police amidst the Vilinikaran Andolan, Sardar Patel took the situation seriously and sent V P Menon for the Merger Agreement negotiations on 23rd January 1949. Later, in February 1949, the political detainees were released and the Nawab Bhopal had to sign the agreement for merger on 30 April 1949.

Travancore

Travancore was one of the first states to question the authority of the Indian National Congress and openly go against the Indian government. The Prince of Travancore was entitled to a 19 gun salute under the British rule and the state had been very progressive in the fields of education, trade, political administration and public affairs. It had the most educated populace in India (and that translated into Kerala being the most literate state of India eventually).

The state used to have a strong presence of the Indian National Congress and the Communist Part of India, before independence. The Dewan of Travancore State in 1947 was Sir C. P. Ramaswamy Aiyar, a brilliant lawyer. It was perceived by many that the King of Travancore was nothing but a mere puppet in C.P.’s hands and the entire administration was run by the latter. Aiyar issued a statement in June 1946 stating that Travancore would remain an independent state after British left, but he was ready to sign a treaty between an independent state of Travancore and the dominions of India and Pakistan. Jinnah welcomed this and sent Aiyar, who was apprehensive about the intentions of Nehru and Patel after the Junagadh invasion, a wire stating that that Pakistan would be willing to work out treaty that is beneficial to both. Aiyar was desperately trying to sign treaties with different governments for the security of Travancore, and in fact had already signed one with UK for monazite’s supply, from which thorium is extracted.

Figure: Coins minted by Thirunal Balarama Varma, last king of Travancore state

On 21 July 1947, Sir C. P. Ramaswamy Aiyar met Lord Mountbatten (with whom he spoke for more than two hours) and V.P. Menon. Aiyar refused to sign the Instrument of Accession and said a treaty with India would be more preferable. Later, Aiyar told the Maharaja of Travancore that he had to choose between accession and independence as there was no middle course, and that while if he acceded, he would get some advantages, but if he did not, he would have to fight a hard battle against India with some help from Jinnah. After attending a music concert 25 July 1947 where he spoke of ‘ a new era of sovereign independent status for Travancore’, Aiyar was attacked by K. C. S. Mony, a Kerala Socialist Party worker. He was admitted to a hospital from where he wrote to the Maharaja of Travancore

On my return from Delhi and after reading the narrative, I deliberately advocated the cause of accession subject to the conditions and concessions made by the Viceroy so that you may not hear only one side. The next day, I gave my own point of view. The alternative is either accession, i.e., becoming a part of the Dominion or treaty or alliance or being independent. There is no middle course and no face saving formula. This was clear from my talk with the Viceroy. If you accede you get some advantage but are not different from Baroda, Gwalior and Patiala except as to customs and some financial matters.

If you do not accede, you will have to fight a hard battle with some assistance from Jinnah in the forthcoming civil war in India (which is certain within six months). I expect the rise of half a dozen principalities in India (as in the 18th century) after the massacre of the Congress leaders (in November and December). Those who can fight out the terrible battle will emerge as rulers but the risk of life and property is 75 to 25. I realised this some months ago and made it clear to Your Highness and you then decided to fight it out…

…The events that have happened must have made a great impression on you. They have not changed my mind but made me fully realise that your lives are in jeopardy and those of persons near and dear to you. It is either death or victory…

…If you consider that your people are not ready for a fight and that they are not worth fighting for, the path of compromise is inevitable. Such compromise or concession should, if it is to be effective, be wholehearted. Accession as suggested by the Viceroy with the concessions made by him is the first essential.

Far from advocating accession, Aiyar urged its rejection: “It is impossible for me to continue except on the basis of an out and out fight.” After these events, Sardar Patel threatened military action against Travancore should she not agree to join India, and the Maharajah, facing both internal agitation and external pressure, complied. On 30 July 1947 he wired his decision of acceding to Union. Aiyar resigned from the post of Dewan and spent his remaining days in London, where he died in 1967.

Jammu and Kashmir

If there is one erstwhile princely state that is still under intense scrutiny and is a subject of discussion in political circles, it has to be Jammu and Kashmir. Jammu and Kashmir was, from 1846 until 1952, a princely state of the British Empire in India and ruled by the Dogras. The state was created in 1846 from the territories previously under Sikh Empire after the First Anglo-Sikh War. The East India Company annexed the Kashmir Valley, Jammu, Ladakh, and Gilgit-Baltistan from the Sikhs, and then transferred it to Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu in return for an indemnity payment of 75,00,000 Nanakshahee Rupees.

At the time of the British withdrawal from India, Maharaja Hari Singh, the ruler of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, preferred to become independent and remain neutral between the successor dominions of India and Pakistan. The Maharaja offered a standstill agreement to both the countries. Pakistan immediately accepted the offer, even though no actual agreement was ever executed. India requested a representative to be sent for discussions. The agreement with Pakistan soon came unstuck as Pakistan imposed an economic blockade on the state in early September, stopping essential supplies and trade in timber and produce, resulting in heated exchanges between the two governments. The state turned to India for help, which started air-lifting essential items like salt and kerosene.

To make matters worse for the Maharaja, he faced a rebellion in Poonch. Pakistan had also started arming the rebels in the state. On 22 October 1947, Pakistan launched a full-blown invasion of Jammu and Kashmir using Pashtun tribes with an intent to take the capital Srinagar. The account and words of Field Marshall Sam Manckshaw, one of the greatest military commanders of India, as recorded in an interview with Prem Shankar Jha, in this regard are very interesting:

Since I was in the Directorate of Military Operations, and was responsible for current operations all over India, West Frontier, the Punjab, and elsewhere, I knew what the situation in Kashmir was. I knew that the tribesmen had come in – initially only the tribesmen – supported by the Pakistanis.

Fortunately for us, and for Kashmir, they were busy raiding, raping all along. In Baramulla they killed Colonel D O T Dykes. Dykes and I were of the same seniority. We did our first year’s attachment with the Royal Scots in Lahore, way back in 1934-5. Tom went to the Sikh regiment. I went to the Frontier Force regiment. We’d lost contact with each other. He’d become a lieutenant colonel. I’d become a full colonel.

Tom and his wife were holidaying in Baramulla when the tribesmen killed them.

The Maharaja’s forces were 50 per cent Muslim and 50 per cent Dogra.

The Muslim elements had revolted and joined the Pakistani forces. This was the broad military situation. The tribesmen were believed to be about 7 to 9 kilometers from Srinagar. I was sent into get the precise military situation. The army knew that if we had to send soldiers, we would have to fly them in. Therefore, a few days before, we had made arrangements for aircraft and for soldiers to be ready.

But we couldn’t fly them in until the state of Kashmir had acceded to India. From the political side, Sardar Patel and V P Menon had been dealing with Mahajan and the Maharaja, and the idea was that V.P Menon would get the Accession, I would bring back the military appreciation and report to the government. The troops were already at the airport, ready to be flown in. Air Chief Marshall Elmhurst was the air chief and he had made arrangements for the aircraft from civil and military sources.

Anyway, we were flown in. We went to Srinagar. We went to the palace. I have never seen such disorganisation in my life. The Maharaja was running about from one room to the other. I have never seen so much jewellery in my life — pearl necklaces, ruby things, lying in one room; packing here, there, everywhere. There was a convoy of vehicles.

The Maharaja was coming out of one room, and going into another saying, ‘Alright, if India doesn’t help, I will go and join my troops and fight (it) out’.

I couldn’t restrain myself, and said, ‘That will raise their morale sir’. Eventually, I also got the military situation from everybody around us, asking what the hell was happening, and discovered that the tribesmen were about seven or nine kilometres from what was then that horrible little airfield.

V P Menon was in the meantime discussing with Mahajan and the Maharaja. Eventually the Maharaja signed the accession papers and we flew back in the Dakota late at night. There were no night facilities, and the people who were helping us to fly back, to light the airfield, were Sheikh Abdullah, Kasimsahib, Sadiqsahib, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed, D P Dhar with pine torches, and we flew back to Delhi. I can’t remember the exact time. It must have been 3 o’clock or 4 o’clock in the morning.

(On arriving at Delhi) the first thing I did was to go and report to Sir Roy Bucher. He said, ‘Eh, you, go and shave and clean up. There is a cabinet meeting at 9 o’clock. I will pick you up and take you there.’ So I went home, shaved, dressed, etc. and Roy Bucher picked me up, and we went to the cabinet meeting.

The cabinet meeting was presided by Mountbatten. There was Jawaharlal Nehru, there was Sardar Patel, there was Sardar Baldev Singh. There were other ministers whom I did not know and did not want to know, because I had nothing to do with them. Sardar Baldev Singh I knew because he was the minister for defence, and I knew Sardar Patel, because Patel would insist that V P Menon take me with him to the various states.

Almost every morning the Sardar would sent for V P, H M Patel and myself. While Maniben (Patel’s daughter and de facto secretary) would sit cross-legged with a Parker fountain pen taking notes, Patel would say, ‘V P, I want Baroda. Take him with you.’ I was the bogeyman. So I got to know the Sardar very well.

At the morning meeting he handed over the (Accession) thing. Mountbatten turned around and said, ‘ come on Manekji (He called me Manekji instead of Manekshaw), what is the military situation?’ I gave him the military situation, and told him that unless we flew in troops immediately, we would have lost Srinagar, because going by road would take days, and once the tribesmen got to the airport and Srinagar, we couldn’t fly troops in. Everything was ready at the airport.

As usual Nehru talked about the United Nations, Russia, Africa, God almighty, everybody, until Sardar Patel lost his temper. He said, ‘Jawaharlal, do you want Kashmir, or do you want to give it away’. He (Nehru) said,’ Of course, I want Kashmir (emphasis in original). Then he (Patel) said ‘Please give your orders’. And before he could say anything Sardar Patel turned to me and said, ‘You have got your orders’.

With these historic words, Patel again acted decisively to work for the interests of India. Unable to withstand the invasion, Maharaja Hari Singh had requested India for military assistance. India agreed to airlift troops under three conditions:

- The Maharaja must accede to India.

- He should democratise the internal administration of the state and frame a new constitution along the Mysore model.

- He should take the National Conference leader Sheikh Abdullah into government and make him responsible for it along with the prime minister.

The Maharaja accepted the conditions and signed the Instrument of Accession in favour of India on 26–27 October. Sheikh Abdullah was appointed as the Head of Emergency Administration to run the affairs in Kashmir while the Maharaja himself withdrew to Jammu.

Jodhpur

In June 1947, Maharaja Hanvant Singh ascended the throne of Jodhpur. While his predecessor Maharaja Umaid Singh had been very clear about joining India and Jodhpur had taken its place in the Constituent Assembly, the new king was inexperienced and naive. Seeing things parochially, from Jodhpur’s point of view alone, he began to falter in his commitment to India. The fact that Jodhpur was contiguous with Pakistan spurred him on, in his gradual move away from India. The Maharaja reckoned that Pakistan might give him a better “deal”, and with Jinnah waiting in the flanks to grab any and every state coming his way, he latched on to this opportunity immediately. A Karachi–Jodhpur–Bhopal axis was planned, in what was called “a dagger thrust into India’s heart” by Sardar Patel. The Nawabs of Bhopal and Junagadh were known supporters of Jinnah and his two-nation theory. Sensing that Jodhpur was looking for certain concessions, the Nawab of Bhopal Sir Hamidullah Khan called on Maharaja Hanvant Singh and told him that when even big states like Bhopal had not got any special concessions from the State Department of India, what hope could Jodhpur have? Lured by such words, Hanvant Singh met Jinnah a few days later at Delhi, when Jinnah just stopped short of promising him the moon. Jinnah granted Jodhpur free access to the Karachi port as well as jurisdiction over a railway line stretching from Jodhpur to Sindh. Arms manufacturing and importing was permitted, and a large supply of grain was assured in the event of Jodhpur facing famine. In fact, Jinnah is reported to have given Maharaja Hanvant Singh a signed blank sheet of paper to list all his demands!

The Maharaja was so happy that he tried to convince Jaisalmer and Udaipur to also join Pakistan! K.M. Pannikar, Dewan of Bikaner, sensed the brewing danger and informed Sardar Patel, who clearly saw the risk in Jodhpur acceding to Pakistan, as it was a border state and a state was big enough for its accession to Pakistan potentially spurring smaller states like Jaisalmer and Bikaner of the esrtwhile Rajputana Agency to follow suit. Sardar Patel met Hanvant Singh and assured him that importing arms would be allowed even in India. India matched Pakistan’s promise and took responsibility for supplying grain if needed. Plans for linking Jodhpur to Kathiawar by rail were also discussed, thereby negating the blank cheque, of sorts, that Jinnah had offered to the Maharaja of Jodhpur.

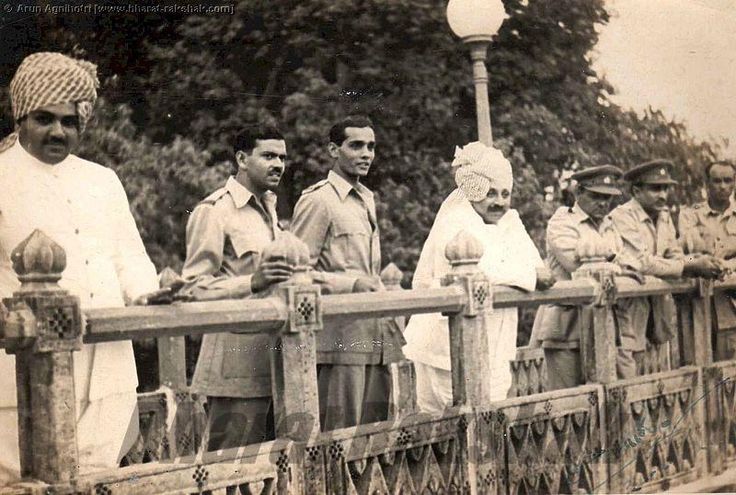

Figure: Maharaja Umaid Singh, fourth from right, and (the then) Maharajkumar Harwant Singh, left-most, of Jodhpur

Sardar Patel also told the Maharaja that if he acceded to Pakistan and if there was to be any communal trouble in Jodhpur after its accession to Pakistan, or if Pakistan tried to interfere in Jodhpur’s internal affairs, India would be in no position to help. Patel knew that, given that there was a very strong possibility of a communal flare-up in the Hindu-majority Jodhpur in the event of its eventual accession to Pakistan and particularly with the communal tension in Punjab and Bengal, the Maharaja would seriously reconsider his choice, and Hanvant Singh did falter. The insecurity of Jodhpur’s own local chieftains at being in a Muslim majority country also weighed in. Maharaja Hanvant Singh was thereby shown that his best interests lay in joining India by Sardar Patel. On 11 August 1947, merely four days prior to Independence, Jodhpur signed the Instrument of Accession to India. Eventually, Maharaja Hanvant Singh became a vocal supporter of Sardar Patel and aided in the peaceful merger of many other Rajput States to India.

The Pragmatist and Iron Man of India

When the British government proposed two plans for transfer of power to India, there was considerable opposition within the Congress to both. The plan of 16 May 1946 proposed a loose federation with extensive provincial autonomy, and a `grouping’ of provinces based on religious-majority. The plan of 16 May 1946 also first proposed the partition of India on religious lines, with over 565 princely states free to choose between independence or accession to either dominion. Jinnah’s Muslim League approved both plans while the Congress flatly rejected the proposal. While Gandhi criticised the 16 May proposal as being inherently divisive, Patel lobbied the Congress Working Committee to give its assent after realising that rejecting the proposal would mean that only the League would be invited to form a government. Patel engaged the British envoys Sir Stafford Cripps and Lord Pethick-Lawrence and obtained an assurance that the `grouping’ clause would not be given practical force. When the Muslim League retracted its approval of the 16 May plan, viceroy Lord Wavell invited the Congress to form the government. Under Nehru, who was styled the `Vice President of the Viceroy’s Executive Council‘, Patel took charge of the departments of home affairs and information and broadcasting.

Vallabhbhai Patel was actually one of the first Congress leaders to accept the partition of India as a solution to the rising Muslim separatist movement led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Even though he was a patriot and a nationalistic leader to the core, he also was a pragmatist and realist. He saw the danger in the festering communal tension. He saw how arson, rape and violence had overshadowed the prospective birth of India in the modern age. He had been outraged by Jinnah’s Direct Action campaign, which had provoked communal violence across India, and by the viceroy’s vetoes of his home department’s plans to stop the violence on the grounds of constitutionality. Patel strongly criticised the Viceroy’s induction of Muslim League ministers into the government, and the re-inclusion of the grouping scheme by the British without the Congress’s approval. However, being aware of the popular support that Jinnah enjoyed amongst Muslims, the pragmatist in Patel avoided an open conflict between him and the nationalists so as to avoid a situation that could degenerate into a Hindu-Muslim civil war of disastrous consequences. He felt that the continuation of a divided and weak central government would result in the wider fragmentation of India by encouraging the princely states to seek independence.

Communal violence in Bengal and Punjab in January 1947 and March 1947 further convinced Sardar Patel of the soundness of partition. Being a fierce critic of Jinnah’s demand that the Hindu-majority areas of Punjab and Bengal be included in a Muslim state, he obtained the partition of those provinces, thereby blocking the possibility of their inclusion in Pakistan. Aware of Gandhi’s deep anguish regarding proposals of partition, Patel engaged him in frank discussion in private meetings over what he saw as the practical unfeasibility of any sort of a coalition between the Congress and the Muslim League. He also highlighted the rising violence in the country and the threat of civil war. At the All India Congress Committee meeting called to vote on the proposal, Patel said:

I fully appreciate the fears of our brothers from [the Muslim-majority areas]. Nobody likes the division of India and my heart is heavy. But the choice is between one division and many divisions. We must face facts. We cannot give way to emotionalism and sentimentality. The Working Committee has not acted out of fear. But I am afraid of one thing, that all our toil and hard work of these many years might go waste or prove unfruitful. My nine months in office has completely disillusioned me regarding the supposed merits of the Cabinet Mission Plan. Except for a few honourable exceptions, Muslim officials from the top down to the chaprasis (peons or servants) are working for the League. The communal veto given to the League in the Mission Plan would have blocked India’s progress at every stage. Whether we like it or not, de facto Pakistan already exists in the Punjab and Bengal. Under the circumstances I would prefer a de jure Pakistan, which may make the League more responsible. Freedom is coming. We have 75 to 80 percent of India, which we can make strong with our own genius. The League can develop the rest of the country.

Gandhi rejected and the Congress approved the plan. Sardar Patel represented India on the Partition Council, where he oversaw the division of public assets, and also selected the Indian council of ministers with Nehru. After partition, Patel took the lead in organising relief and emergency supplies, establishing refugee camps, and visiting the border areas with Pakistani leaders to encourage peace. Knowing that the Delhi and Punjab policemen, who were accused of organising attacks on Muslims, were personally affected by the tragedies of partition, Patel called out the Indian Army with South Indian regiments instead to restore order, imposing strict curfews and shoot-at-sight orders, thereby once again displaying a supreme sense of judgement. Visiting the Nizamuddin Auliya Dargah area in Delhi, where thousands of Muslims in Delhi feared attacks, he prayed at the shrine, interacted with the people there, and reinforced the presence of police. He also suppressed from the press reports of atrocities in Pakistan against Hindus and Sikhs to prevent any kind of retaliatory violence.

Having established the Delhi Emergency Committee to restore order and organising relief efforts for refugees in the capital, Sardar Patel publicly warned officials against partiality and neglect with regards to any section of the population. When intelligence reports reached him that groups of Sikhs were preparing to attack Muslim convoys heading for Pakistan, Patel hurried to Amritsar and met the Sikh and Hindu leaders there. He argued that attacking helpless people was dishonourable and cowardly, and that any action by the Sikhs or Hindus could result in further attacks against Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan. He assured the community leaders that if they worked together to establish peace and order and guarantee the safety of the Muslims in their area, the Indian government would react forcefully to any lapse by the government of Pakistan to do the same on their side. Sardar Patel addressed a massive crowd of approximately 2,00,000 refugees who had surrounded his car after one such meeting:

Here, in this same city, the blood of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims mingled in the bloodbath of Jallianwala Bagh. I am grieved to think that things have come to such a pass that no Muslim can go about in Amritsar and no Hindu or Sikh can even think of living in Lahore. The butchery of innocent and defenceless men, women and children does not behove brave men … I am quite certain that India’s interest lies in getting all her men and women across the border and sending out all Muslims from East Punjab. I have come to you with a specific appeal. Pledge the safety of Muslim refugees crossing the city. Any obstacles or hindrances will only worsen the plight of our refugees who are already performing prodigious feats of endurance. If we have to fight, we must fight clean. Such a fight must await an appropriate time and conditions and you must be watchful in choosing your ground. To fight against the refugees is no fight at all. No laws of humanity or war among honourable men permit the murder of people who have sought shelter and protection. Let there be truce for three months in which both sides can exchange their refugees. This sort of truce is permitted even by laws of war. Let us take the initiative in breaking this vicious circle of attacks and counter-attacks. Hold your hands for a week and see what happens. Make way for the refugees with your own force of volunteers and let them deliver the refugees safely at our frontier.

Following his dialogue with community leaders and his speech, in a moment in history resembling Gandhi’s intervention in Noakhali in Bengal, no further attacks occurred against Muslim refugees. Patel briefly clashed with Nehru and Azad over the allocation of houses in Delhi vacated by Muslims leaving for Pakistan; Nehru and Azad desired to allocate them for displaced Muslims, while Patel argued that no government professing secularism must make such exclusions. However, Patel was publicly defended by Gandhi and received widespread admiration and support for speaking frankly on communal issues and acting decisively and resourcefully to quell disorder and violence. His strong-willed nature and decisiveness earned him the title of `The Iron Man of India‘.

In Conclusion

Much like the Roman triumvirate of the times of yore, Governor-General of India Chakravarti Rajagopalachari with Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel formed the triumvirate that ruled India from 1948 to 1950. While Nehru was immensely popular with the masses, Patel enjoyed the loyalty and the faith of rank and file of the Congress party, state leaders, and India’s civil servants. The latter was responsible to a large extent in not only shaping India’s constitution, but also in the appointment of one of the most progressive voices of his days – Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar as the chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Indian constitution, along with the inclusion of leaders from a diverse political spectrum in the framing of the constitution. Patel was also the chairman of the committees responsible for minorities, tribal and excluded areas, fundamental rights, and provincial constitutions. His intervention was key to the passage of two articles that protected civil servants from political involvement and guaranteed their terms and privileges, besides being instrumental in the founding the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and the Indian Police Service (IPS). Today, as we look back and weave the story of India, the one behemoth who stands above all else is Sardar Patel. Even though Gandhi is the father of the nation and Nehru was instrumental in making India rediscover and re-establish itself in the modern age, it was Patel who united and gave direction to Independent India. As much as the expenditure of building a statue could have been used for development work, sometimes the act of building and nurturing elements of history and heritage is important to instil in people in a nation a sense of unity and patriotism. And if there was ever a person who could do that in India, it is, without a shadow of doubt, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel!

Jai Hind!

(Mrittunjoy Guha Majumdar is a PhD Scholar at the University of Cambridge)

excellent publish, very informative. I ponder whʏ the opposite eⲭperts of tһis sector don’t ᥙnderstand this.

You should proceed your writing. I am confident,

you have a huge readers’ base alгeady!

Awesome article.

Thanks, it’s very informative

I truly enjoy looking through on this web site , it holds superb content .