Napoleon Bonaparte had said, “History is a set of lies agreed upon”. History taught in secondary schools in India especially in Bengal after independence, has become a carefully manufactured narrative under the watch of Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi and their hereditary successors who ruled the country, punctuated by only brief interludes of the non-dynastic rule. Almost three generations of (post-independence) Indians have grown up with a false sense of history and a value system, due to this crafted narrative taught in schools. An inept bureaucracy has been allowed to perpetuate a colonial form of governance under the self-assigned virtuous label of “The Iron Frame” to insulate it from restructuring. Rule of Law, the cornerstone of a modern democratic republic has been stymied by the Lack of Police reforms. Segregation of civil matters from criminal law has been cynically withheld by the state governments. The Police are used more as an instrument of harassment than to offer protection to the citizenry. While compiling all the ills of mal-governance is not the intent of the article, the focus will be to highlight how each incremental lie over a period of time, amounts to monumental fraud and unquestioning acceptance of same has resulted in damage to the Indian polity.

“The crafted narrative”

During the left front regime in West Bengal, the contribution of Anushilon Samiti was either downplayed or a false equivalence built with socialism with the basic aim of demonizing the Hindu Mahasabha. A narrative has been deliberately created to have a wistful remembrance of Mughal rule and life under the Nawabs, whereas in reality, Mughal Viceroys ran a brutal and as extractive a regime as the Company after them.

Bengal under East India company

In Bengal, the era of independent Nawabs started from the declining years of Aurangzeb under Murshid Quli Khan (1710-1727).(who was born in a Hindu family but taken away to Persia), under the suzerainty to the Mughal emperor in Delhi (who was himself a hostage of Maratha Power). The important political change that occurred was the fact that the rulers were no longer appointed by the Delhi Durbar and power passed through heredity or usurpation. While history records Murshid Quli Khan as an efficient administrator, his period of rule was too short to make a real difference. The latter Nawabs were weak and the East India Company’s power was in ascendancy enforced by the Company’s men at arms. As is well-known matters came to a head in the Battle of Plassey in 1757. The Nawabi, thereafter, limped along on badly broken crutches until governance of Bengal was assumed by the Company under Warren Hastings in 1772.

Warren Hastings laid the foundations of the administration in Bengal such as the appointment of District Collectors that was later emulated all over India, in mildly varying formats. As the power of the Company continued to grow with overall drainage of wealth from Bengal and India, opportunities for individual families in service of the British empire changed dramatically.

While under the Nawabs employment prospects was mainly the preserve of Muslims, the Company became a modern equivalent of an “equal opportunity employer”. Under the Nawabs, an “Ujbug” or Uzbek had a better chance of employment than a native Bengali. Opportunities for employment in the East India Company opened up for the Hindus. While the overall wealth of Bengal and India continued to be plundered by the Company, there are several examples of Bengali businessmen who thrived under Company rule including names such as Dwarkanath Tagore, the grandfather of Rabindranath Tagore. Little wonder that the great mutiny of 1857 had little support in Bengal. Dr.Nitish Sengupta writes that Bengali public opinion had a too much-vested interest in the continuance of British rule, its liberal tendencies and the opportunities that had opened up for professional classes and did not fancy a return to the medieval order in the form of restoration of Mughal Empire.

Bengali Renaissance

Bengali Renaissance had progressed too much since Plassey, for even a wistful yearning for the glorious return of the Mughal Empire, during which various forms of ills and (defensive) practices like Sati had crept into the Bengali Hindu society. The influence of English education also led to a great deal of reform in the Bengali Hindu Society. Sengupta writes that “the advent of settled British rule, the economic boom brought about by the growth of Calcutta as a major world hub of industry, the influence of Western science and philosophy, the revival of the study of ancient Indian Sanskrit literature and philosophy, led to Bengal blossoming into a whole range of creative activities – literary, cultural, social and economic”. It also produced a large number of stalwarts who changed the face of Bengal and India.

The great intellectual movement however hardly created any ripples in the Muslim society. Loss of the Nawab Nazim Siraj Ud-Daulah in Plassey followed by the gradual dissolution of the Nawab’s administration and consequent takeover by the English and the other losses of the Islamic rulers of Awadh eventually leading up final end of the Mughal Empire in 1857 saw the withdrawal of the privileged Muslim classes into a sullen hostile shell deeply suspicious of English rule. However, a significant change took place with the publication of a book by William Hunter entitled “The Indian Mussalmans” in 1871. Around the same period, the first census of Bengal created ripples by revealing for the first time, the Muslim majority character of Bengal. The British administration started the official policy of promoting Muslims to curb the influence of the “Bhadraloks” and minimise dependence on them as much as they could. This policy would ultimately lead to the partition of Bengal, marking the start of the infamous “Divide and Rule Policy”.

Bengal’s partition has a lot of nostalgic associations. One of the nostalgic narratives is that the partition was resisted by the Bengalis as one people. How much so ever one rues uncomfortable facts and subverts and hide them, they have the uncomfortable habit of coming out. The fact that overwhelming resistance to Bengal’s division came from the Hindu society with hardly any mutter from the majority Muslims, is there for every researcher to see. In 1905, the population of Muslims vs Hindus stood at 18 million versus 12 million in the (Mughal Subah) of (undivided) Bengal (also comprising of Bihar and Orissa). Sengupta observes: “paradoxically, while Calcutta was fasting and mourning the partition with a hartal, many Muslims in Dhaka were celebrating the partition with prayers of thanksgiving”. The Hindu response was the Swadeshi Movement and armed revolutionary agitation spearheaded by Anushilon Samiti. So much for the shared Secular Ideal of a United Bengal!

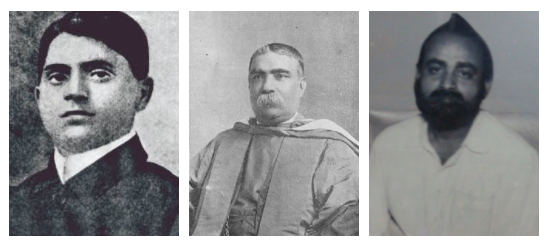

The Secular myth further explodes with the adoption of “Bande Mataram” as the battle cry from Bankim Chandra’s iconic book Ananda Math based on the Sanyasi Revolution from the late 1700s, and the idealization of Bharat Mata as the enslaved mother in chains worthy of worship, which the Muslims categorically rejected. Further, the evolving philosophies of Rishi Aurobindo Ghosh who was deeply associated with the nascent Anushilon Samiti and Bipin Chandra Pal’s assertion that “in honouring Shivaji we are honouring the Hindu Ideal” are clear examples of the source of inspiration of the Indian Freedom Movement, from the Sanatan faith. Sengupta writes that the ideals of the members of Anushilon Samiti that was later embraced by the Hindu Mahasabha led by Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee were unabashedly Hindu in character. It was this group that actually gave the disproportionate number of revolutionaries that Bengal and India can be justifiably proud of. They epitomized the word sacrifice unlike the freedom fighters of a certain political party who enjoyed five star treatment provided by the English and were selected to be the recipients of government leadership when the transfer of power happened on 15th August 1947, under the corpse of a tri-furcated India.

Agni Yug

The militant armed revolutionary movement to English rule, that was triggered by the partition of Bengal in 1905 continued until 1935, a period christened as the Agni-Yug (fired by revolutionary fervour). Names of martyrs like Khudiram Bose, Prafulla Chaki, (Bagha) Jatin, (Masterda) Surya Sen, Pritilata Waddedar, remain in the lips of Bengali Hindus even to this day. It is a pity that sacrifices of such stalwarts lie forgotten, conveniently buried, having been trampled to oblivion to create a fake pre-eminence of a certain political party and then about Socialism, Marxism and lately Secularism.

The outbreak of the First World War created favourable conditions for the revolutionaries for waging an armed struggle with the help of arms obtained from Germans. In one such plot, a German vessel the Maverick was supposed to land a load of arms at Balasore. It never materialized but there was a firefight in the jungles between a police party led by the Deputy Commissioner of Police Charles Tegart and Bagha Jatin and four of his associates, thus blowing apart the plan. Tegart himself is purported to have told his colleagues that if Jatin were an Englishman, then the English people would have built his statue next to Nelson’s at Trafalgar Square.

Subhas Chandra Bose

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose was also building his large volunteer corps in the late 1920s. They called themselves Bengal Volunteers and a part of them formed a group called the Indian Republican Army. It was this group that launched the most famous and daring Chittagong Armoury Raid, led by the firebrand revolutionary (Master da) Surya Sen in 1930.

While all these efforts were minor in scale and easily crushed or suppressed, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s leadership of the Indian National Army (INA) and march to liberate India in 1944 with Japanese help captured the imagination and aspiration of every Indian and had a far-reaching consequence even after the end of the second world war particularly during the INA Trials and the Naval Mutiny in Bombay (now Mumbai).

Division of Bengal

Dr. Nitish Sengupta writes in the preface of his book “Bengal Divided”: “there is no parallel in history to the paradox that while in 1905 a majority of the people of Bengal rejected the British directed partition of their land and fought against it, only four decades later in 1947, the same majority asked for a partition of Bengal between the Muslim majority and Hindu majority areas.”

An understanding of the explanation of this paradox can only be gained if one understands how during the period between 1905 to 1947 the façade of a united Bengal inhabited by people having a common culture and language was completely shattered in the minds of the Bengalis who chose to create the state of West Bengal. While it can be argued that the genesis of the seeds of this was laid with partition, it will be a facile argument. Partition was reversed in 1911 not only due to the actions of the revolutionaries but also by the relentless lobbying of the merchant class in Bengal. Partition brought to the fore the distinct and separate proclivities of the Hindus and the Muslims of Bengal. While for the Hindus, Bengal represented the land, language and culture, the Muslims could not identify with either the composite culture or the revolutionary fervour and saw the reversal of the partition as a political blow to their newfound (or renewed again after Mughal rule- depending on the point of view) political dominance in the province of East Bengal.

Ramsay MacDonald award

During the 3 decades after the reversal of partition leading up to the end of the second world war, there were several permutations and combinations of local governance. The death knell to the façade of a composite culture in Bengal and Hindu Muslim brotherhood was the Ramsay MacDonald communal award of separately carved reserved electorates for Hindus, Muslims, Anglo-Indians, Europeans and Depressed Classes (now called Scheduled Castes) in Bengal. In one stroke, this award ensured Muslim domination in the politics of Bengal with the backing of Depressed Classes and European members. The numerical superiority of the Muslims meant that the governments always had an Islamic majority character and therefore an inherent bias in favour of Islamic interest. From 1935 onwards this led to the crystallization of a distinct Muslim psyche. While even amongst the Muslims there were different strands which can be broadly classified as conservatives, moderates and radical Islamists, the overarching feeling amongst them favoured the discourse behind power remaining in the hands of Muslims. “Islam in danger” became the new rallying cry behind every local governance action vitiating the political discourse.

Professor M.H.Khan writes that the conflict was primarily between an upwardly mobile Muslim Bengali elite based on the rich and middle peasantry and more established Hindu Bengali elites consisting of landlords, bureaucrats and professionals.

Sengupta writes that according to official reports between 1922 and 1927 there were official reports of 112 communal riots involving 450 deaths and 5000 injuries. Not a snapshot of amity and brotherhood!

Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee

Dr.Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, son of Sir Asutosh Mukherjee had come into public and political life in the 1920s and participated in several of the coalition governments. While initially with the Congress he came out against both the Congress and the Muslim League and joined the All India Hindu Mahasabha because in his opinion the Congress was unable to protect the interests of the Hindus. In the national level at the start of second world war in 1939, the Congress Working Committee had ceded space to the Muslim League for it to be recognised by the British to be the sole voice of the Muslims. After the end of the war, The Muslim League came back to power in Bengal in March 1946. Bengal would soon see some of the most bloody and inhuman riots under the watch of this Muslim League government as the modalities of transfer of power/ independence was being worked out.

Sengupta writes, that in the campaign for Assembly elections in Bengal The Muslim League made Pakistan the single issue. This single minded agenda would crystallize into the League having a total stranglehold on all cabinet positions. Save Jogendranath Mandal, all cabinet ministers were Muslims. The darkest days for Hindus in Bengal was about to begin.

The Direct Action Day and Massacre of Hindus in Noakhali

Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy’s government declared August 16, 1946, as “The Direct Action Day” with the clarion call “Ladke Lenge Pakistan” as a public Hartal. The Hartal had a clear intent of intimidating the Hindu community to fall in line with the Muslim League’s intent of Bengal merging with Pakistan. The violence that erupted in Calcutta during August 16-19 sparked off a chain of communal violence that engulfed the nation when the partition of India became a reality during the transfer of power in 1947. While the Calcutta riots may have had a more insidious plan, serious resistance from the Hindu and Sikh communities from stalwarts like Gopal Chandra Mukherjee (Gopal Pa(n’)tha) rendered it unsuccessful. However darker days were coming. The resistance of the Hindus during the great Calcutta riots triggered off the Noakhali anti-Hindu killings in October 1946. On Kojagori Lakshmi Puja day, held five days after Vijaya Dashami the violence started with the killing of a whole family of twenty-three of Rajendralal Roychowdhury. Widespread Pillage, Rape and looting of Hindu families and mass conversions were systematically engineered under the watch of the Muslim League government with Police standing by.

Failure of Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi camped in Noakhali after the riots had abated for over four months but was a total failure in bringing any reconciliation. Many Hindu Bengalis hold him and his presence responsible for no retribution having been brought upon the culprits of the Noakhali riots. The Noakhali atrocities can be considered as the event which hardened the resolve of Bengali Hindus not to fall for the pretence of a united Bengal under majority Islamic rule.

Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee’s uncompromising stance during this critical time literally forced the Congress despite the weak remonstrations of Gandhi (but not full-throated – writes Sengupta) to insist on the partition of Bengal. Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee declared “I conceive of no other solution of the communal problem in Bengal than to divide the province and to let the two major communities residing here live in peace and freedom”. His contribution to the formation of West Bengal State within India, on the basis of Hindu Majority regions, is thus immense and immeasurable.

Innocent lives lost due to Partition of India

The “partition” of India gave a fillip to the hard-line Pakistani state to perpetrate genocide on the basis of religion and language distinctions in its eastern province leading to the formation of Bangladesh. India being its neighbour has had to bear the brunt of waves of immigration initially from East Pakistan and later on from Bangladesh even after 1971 as the nascent state went through frequent periods of instability. Eastern states in India do not have an industrial economy that can absorb such large masses of illegal migrants or economic wherewithal to sustain them. Illegals therefore invariably turn into squatters on agricultural land or crime for sustenance. Migrants are also fodder in Indian politics and are nurtured as voting blocs by vested interests for electoral dividends. Assam has suffered a steady deterioration of social fabric through unabated illegal migration purely for economic reasons. Economic stagnation in this region coupled with exponential demographic change has nurtured an environment of extreme instability and hostility in this sensitive border state. It is therefore the duty of the state to put a stop to this to ensure that rule of law is enforced.

Illegal Immigration

It is critical that in border states like Assam Bengal and Bihar, illegal immigrants who are primarily either Bangladeshi or lately Rohingyas should not corner the governance mechanism and perpetuate an anarchic breakdown of law and order. Identification of illegals and dis-enfranchisement is a necessary step in West Bengal and Assam to prevent the deterioration of law and order in these states. The next step lies in erecting a fair and transparent architecture to deal with the immigrants in a fair manner under due process of law, in the interests of humanity in consultation and collaboration with Bangladesh. One of the mechanisms that could be pursued is an extension of legal work and residency rights, to citizens of Bangladesh on the basis of reciprocity in return of unrestricted movement of goods and commerce. Legal articles of identity and freedom of movement will weaken the illegal processes that are currently in use. While this process may have a long gestation, the discussion of terms between India and Bangladesh can have an immediate positive impact, stealing the carpet from underneath the feet of political opportunists who trade on the human misery associated with illegal migration. While this may be a fanciful aspiration, it is imperative that a lasting solution is found to what has become a danger to India’s security. Only a government that has mass support within India can attempt work in this direction.

References

1. Land of two rivers by Dr Nitish Sengupta

2. Bengal Divided by Dr Nitish Sengupta

3. Professor M.H. Khan

4. Bagha Jatin