Trinity College and Christs College stand among the very best of colleges across the world when it comes to legacy, in terms of alumni, and the maintenance of standards even today. As I go from one (Christs, as a PhD scholar) to another (Trinity, as a postdoctoral affiliate), I find a whole new world that is so rich in its heritage. If Christs was the home for greats like Darwin, Milton, Oppenheimer and Mountbatten among its rank of alumni, Trinity has seen the likes of Newton, Bohr, Amartya Sen and Bertrand Russell. The former may have pipped the latter in this year’s Tompkin’s Table, but Trinity has a unique place in the university even today, with members of Trinity having won 33 Nobel Prizes.

Me, with some friends, in front of the Great Fountain, Trinity College

Recently I got the opportunity to visit the famous Wren Library of Trinity College. The library contains many notable books and manuscripts, many of which were bequeathed by past members of the college. The Wren Library houses 750 incunabula, the Capell collection of Shakespeariana, the Rothschild collection of 18th century literature, the Kessler collection of livres d’artistes, and over 70,000 books printed before 1820, as per college sources. Trinity College also possesses an ever-increasing collection of modern manuscripts ranging the manuscript of Bertrand Russell’s The Implications of the H-bomb to A. A. Milne’s manuscript of Winnie the Pooh.

For starters, it contains a number of important books, manuscripts and artifacts related to Isaac Newton.

Newton’s own copy of the first edition of his Principia Mathematica

Newton’s notebook and the place where his walking stick is kept

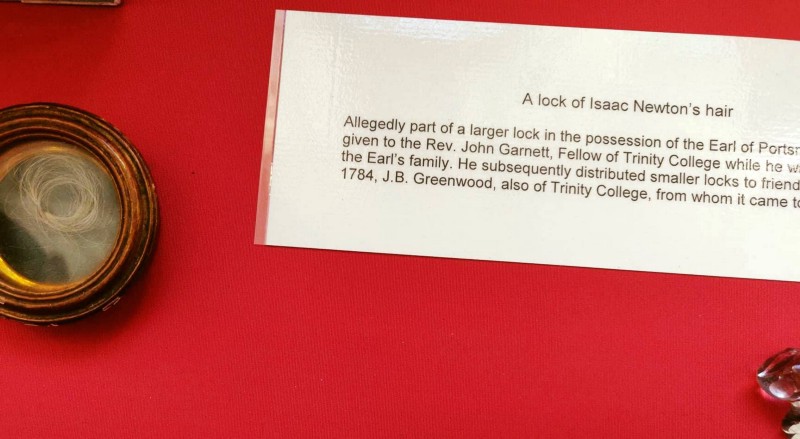

A lock of Newton’s hair!

In June 1661, Isaac Newton was admitted to Trinity, where he started by paying his way by undertaking the duties of a valet before being awarded a scholarship in 1664, which guaranteed him four more years in the college until he received his MA. It is interesting to note that at that time the college’s teachings included primarily the works of Aristotle, Descartes and Galileo, which Newton studied. He is said to have set down in his notebook a set of questions, or a series of ‘quaestiones’ as he put it back then, about mechanical philosophy. In 1665, he discovered the generalised binomial theorem while still being part of the college, and slowly began to develop a theory of mathematics that would eventually become calculus! Newton obtained his BA degree in August 1665. Due to the precautionary closing of the college due to the Great Plague, Newton had to undertake private studies in his home for the next two years, when he developed his theories of mechanics, optics, calculus and gravitation.

Besides Newton’s works, one other set of works in the Wren Library that caught my attention were the letters by Srinivas Ramanujan to the British mathematician G. H. Hardy.

Srinivas Ramanujan’s letter to G. H. Hardy

Another letter by Srinivas Ramanujan to G. H. Hardy

Ramanujan was a veritable genius who made substantial contributions to number theory, infinite series and continue fractions, without much formal training. In 1913, Ramanujan began a correspondence with the British mathematician G. H. Hardy at the University of Cambridge, England. Recognising the extraordinary talent of Ramanujan and the work the latter had sent to him as samples, Hardy arranged for Ramanujan to travel to Cambridge. During his short life of 32 years, Ramanujan independently found almost 4000 mathematical results, with the results on the Ramanujan Prime, partition formulae and Ramanujan theta function standing out. He became one of the youngest Fellows of the Royal Society (FRS) and the first Indian to be elected a Fellow of Trinity College, University of Cambridge. Unfortunately he passed away in 1920 due to what is now believed to have been hepatic amoebiasis. Trinity college has the ‘lost notebook’ of Srinivas Ramanujan in its archives.

Going back a fair few centuries, another major work that the Wren has is the great 12th century Eadwine Psalter from Christ Church Canterbury.

The great 12th century Eadwine Psalter from Christ Church Canterbury

This magnificent manuscript was formerly known as the Canterbury Psalter. It is now named for the scribe, Eadwine, a monk of Christ Church Canterbury where the Psalter was made. It is an illustrated copy of the Psalms in three Latin versions with translations into Old English and Anglo-Norman French. Eadwine is pictured full-page at the end of the manuscript accompanied by the inscription: “the prince of scribes … whose genius the beauty of this book demonstrates”. The Eadwine Psalter was produced and remained at Christ Church for most of the medieval period until it was given to Trinity College Library by Thomas Nevile, Dean of Canterbury and Master of Trinity College.

The library also holds some famous works of Christs alumni! It has a collection of autograph poems by John Milton. The British Library mentions the following about this rare manuscript:

This highly valued manuscript, owned by Trinity College, Cambridge, is John Milton’s working notebook. It has early notes on Paradise Lost from around 1640, revealing how Milton’s ideas evolved, long before the poem was completed in 1665. Rather than being struck by one moment of inspiration, he toys with different characters and tries out different genres — tragic and dramatic. This raises important questions about what Milton kept or re-ordered in his final epic poem, and how he used dramatic features such as soliloquy and dialogue.

On f. 35, Milton jots down several cast lists for a biblical drama about Adam and Eve’s fall. He seems inspired by morality plays, in which characters such as ‘Death’ and ‘Faith’ personify virtues and vices. Alongside Adam, Eve and Lucifer, Milton considers whether to include Moses, Michael, ‘the Evening Starre’ and a Chorus of Angels. He also notes ideas for ‘other Tragedies’ on biblical themes, such as ‘The flood’ and ‘Adam in banishment’.

Just under the line that divides the page, you can faintly see Milton’s first use of the title ‘Paradise Lost’. He then gives a brief outline of a five-act drama, opening with a debate about ‘what should become of man if he fall’, and ending with Adam and Eve being ‘driven out of Paradice’.

The notes are part of a folio notebook, known as the Cambridge or Trinity manuscript, which can be seen in full here. It contains drafts of early poems including the elegy ‘Lycidas’ (1637), as well as a masque called Comus (first performed in 1634). Many pages, including those shown here, are written in Milton’s own hand. Others are the work of different scribes, who worked for Milton after he went blind in around 1652.

Among the other Christs alumni, Darwin is featured in a copy of the first edition of his Origin of Species.

The Milton Manuscript at Trinity (Picture Courtesy: Trinity College Archives)

Another literary giant who is featured in the Wren is Shakespeare. Particularly in a Capell Collection of Shakespeare’s play. Trinity College describes the manuscripts as follows

Edward Capell was an inspector of plays in the eighteenth century, responsible for reading new playscripts and censoring any material considered scandalous or politically sensitive. He took it upon himself to investigate the ‘original’ versions of Shakespeare’s plays and in 1767–68 he published his landmark edition, in ten volumes. In 1779 Capell gave 245 volumes to Trinity, where they have remained ever since.

The Rape of Lucrece was printed in London by Peter Short for John Harrison in 1598 and Venus and Adonis was printed by I. P. in London in 1620. There is only one other known copy of each of these editions, besides the Trinity college copies.

The Rape of Lucrece from the Capell Collection of Shakespeare’ works in Trinity College (Picture Courtesy: Trinity College Archives)

The library also holds several notebooks of Ludwig Wittgenstein, the famous Austrian-British philosopher.

The college archive also comprises of the administrative papers created and received by the college and its predecessors in the transaction of their business. Today Trinity College is one of the richest entities in all of the United Kingdom. This happened due to the massive endowments by various patrons, particularly King Henry VIII. Much of the early material in the Wren relates to Michaelhouse and The King’s Hall, two of the foundations dissolved by Henry VIII when he established Trinity. There is no consolidated catalogue, but an index to the estate records exists and a finding-aid for the volumes in the archive is in progress.

All in all, heeding the call of the Wren was a memorable experience that I shall always cherish.

The legacy of Trinity lives on!